Africa on Screen: The Problem with Hollywood’s Accent, Storytelling, and the 'Single Country' Myth

Africa on Screen: The Problem with Hollywood’s Accent, Storytelling, and the 'Single Country' Myth

In Hollywood, Africa often plays the same role: a monolithic land of wild animals, war-torn villages, noble tribes, or desperate refugees. For decades, African stories on Western screens have been filtered through a distorted lens that overlooks nuance, erases diversity, and reinforces outdated power dynamics. But perhaps one of the most consistent, if subtle, weapons of this misrepresentation is the “African accent.” Flat, vaguely West African, often broken English. It is a voice that many Africans themselves do not recognize.

When paired with the lazy tendency to refer to Africa as a single country, this accent becomes more than a vocal affectation; it becomes a symbol of how the continent is misunderstood, flattened, and frequently ridiculed. Hollywood’s depiction of Africa has long been a mirror reflecting not Africa itself, but the West’s limited imagination about it.

Let’s start with the accent, an element of identity that is personal, regional, and deeply cultural. Africa is home to over “ 2,000 languages” and countless dialects. Nigeria alone has over 500 languages, while Kenya, Ethiopia, and Cameroon host dozens of linguistic communities, each with unique inflections, grammar, and tone. Yet, time and again, Hollywood distills this incredible diversity into a generic, vaguely West African accent, often delivered by non-African actors.

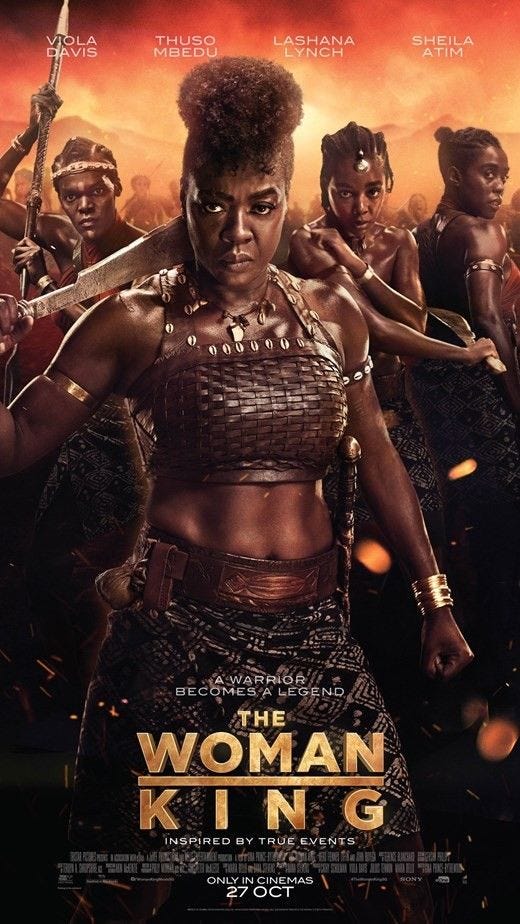

When these accents appear, they’re rarely used to reflect dignity or strength. Instead, they often signal simplicity, comedic relief, or inferiority. In movies like “Coming to America” (1988), the accent is played for laughs as a caricature of African royalty, complete with exaggerated vowels and formal English. In many action films, African characters who deliver warnings or background information do so in broken English, their words often lost behind dramatic music or edited for minimal importance.

What makes this especially damaging is that these accents are not grounded in authenticity, but in Western perceptions of what “African” sounds like. The result is a disembodied, unrooted vocal style that becomes its own stereotype used repeatedly, whether the story is set in Ethiopia, Senegal, or a fictional land like Wakanda. In real life, Africans are polyglots. They speak multiple languages, often fluently: local dialects, colonial languages like English or French, and increasingly, global languages like Mandarin or Arabic.

Yet, when African characters speak, their voices are made to sound alien. Accent becomes a tool of separation signaling that the character is “other,” foreign, and different.This representation has a quiet but lasting impact. When a child grows up hearing their accent mocked or manipulated on global platforms, they begin to associate that accent with shame. Many African immigrants in the UK or U.S. speak of being teased in school for their pronunciation or told to “speak properly.” Over time, they may begin code-switching, adjusting their speech to sound more Western, often abandoning the unique musicality and pride of their native tones.

The damage is not just individual, it's generational. African parents may encourage their children to speak English at home, leaving behind native languages for fear of judgment or exclusion. Entire cultural expressions, proverbs, idioms, oral histories are lost in the process. Accent, in this context, is not just how you sound; it becomes “how you belong”. And if Hollywood keeps reinforcing the idea that African accents are undesirable or funny, it makes the journey of belonging even harder.

The issue of the accent feeds into a larger problem: Hollywood’s persistent belief that Africa is one homogenous place. In movie after movie, characters refer to “going to Africa,” as if the entire continent were one unified space. Whether the scene is set in Ghana or Uganda or an invented country, it’s often shown through the same tropes: dusty roads, drumming in the background, smiling children chasing soccer balls, and a giraffe in the distance.

This flattening of 54 distinct countries into a single idea is deeply problematic. It strips away history, politics, geography, and context. Films like “The Lion King” (1994) while beloved present Africa as a mystical wilderness with no people. Other films like Tears of the Sun , Hotel Rwanda, or The Constant Gardener center around chaos, genocide, or corporate exploitation, often with white characters driving the narrative.

Even when the setting is specific, the story is not. In Black Hawk Down. The Somali civil war becomes a backdrop for U.S. military valor. In Out of Africa, Kenya is portrayed through the lens of colonial romance. African characters often have no interior lives, no dreams or complexity. They exist to either suffer or assist the Western protagonist.

A recurring pattern in Hollywood’s Africa narratives is the “white savior”:A Western character who arrives in Africa to rescue, teach, or redeem. This trope reinforces the idea that Africans are incapable of solving their own problems. Whether it’s The Last King of Scotland, Blood Diamond, or Machine Gun Preacher, the story centers the white perspective, while African characters are sidelined even in their own struggles.This selective gaze continues to define Africa by its lowest moments. Where are the African love stories, rom-coms, tech thrillers, or political dramas that don’t involve coups and child soldiers? Where are the movies set in Johannesburg’s art scene, Lagos’s fintech boom, or Dakar’s fashion world?

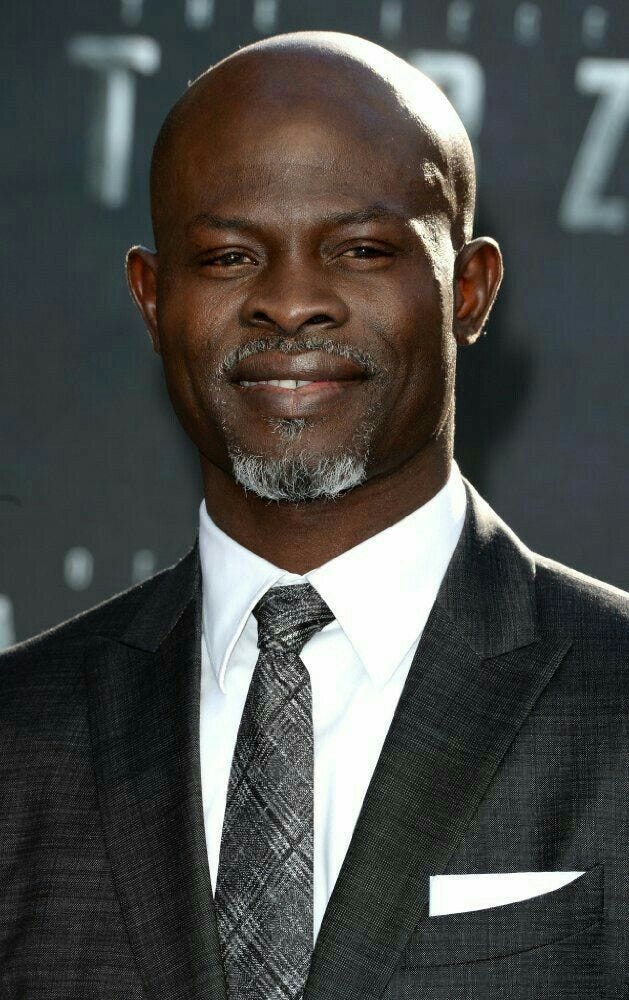

By refusing to tell these stories, Hollywood keeps Africa frozen in time.Ironically, there has been a rise in African representation in Hollywood over the last decade but much of it still operates under Western control. African actors like Lupita Nyong’o, John Boyega, and Danai Gurira have found success, but they are often limited to roles that require some level of “Africanness” to be palatable. Even in Black Panther , the celebration of African culture was designed for a Western audience, with fictional languages and combined cultures used for cinematic effect.Wakanda, though empowering in many ways, was still “a fantasy”. It presented an idealized Africa untouched by colonialism, something that does not exist. While it was a powerful counter-narrative, it was not necessarily reflective of real African life today.

There is hope, though. The rise of streaming platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Showmax has created space for more “authentic African stories” to be told by Africans. Productions like Blood & Water (South Africa), King of Boys(Nigeria), and Queen Sono show African youth, politics, and power with nuance and style.More African filmmakers are also gaining recognition at global festivals. Directors like Mati Diop, Wanuri Kahiu, and Akin Omotoso are breaking boundaries, telling complex stories rooted in African experience often with native languages, local actors, and layered scripts.

Still, funding remains a challenge. Global distribution often favors stereotypes. And even with platforms like Netflix investing in African content, the marketing and global rollout rarely match that of Western shows.

For Africans living abroad, especially young creatives, the tension is even more complicated. They often find themselves straddling two worlds: trying to reclaim their identity while surviving systems built on exclusion. Many use spoken word, fashion, film, or online content to challenge dominant narratives.

Social media has become a tool for empowerment. Nigerian skit makers, South African TikTokers, and Kenyan YouTubers are showing the world real African humor, style, and thought. These creators challenge Hollywood’s script not by shouting, but by showing. They create beauty and relatability out of everyday African life, proving that our stories are not just valid, they're vibrant.

If Hollywood is to grow beyond its outdated lens, it must:

1. Invest in African stories told by African creatives, not just in Africa, but in the diaspora too.

2. Respect linguistic diversity by employing dialect coaches, translators, and native speakers.

3. Stop flattening Africa, be specific about settings, cultures, and history.

4. Diversify narratives, not every African story is about pain. Tell stories about innovation, love, friendship, rebellion, and fun.

5. Hire African talent behind the scenes as writers, editors, costume designers, and cinematographers.

Above all, Hollywood must listen. Not just to what sells but to what’s true.

Who tells the African story matters. And for too long, it has been told by those who do not know the languages, the people, or the land. Accent is more than pronunciation; it is identity. Misused, it becomes a tool of distortion. Flattened narratives become tools of invisibility.

But Africans are no longer silent. A new generation is speaking up not just with words, but with films, songs, scripts, and stories. They are saying: We are not a country. We are not a stereotype. We are not waiting for your permission.

We are here and we are telling our stories.